Before use, a machine in the food industry must obviously be clean. Cleaning is therefore part of the general management measures within the HACCP plan. Nevertheless, things occasionally go wrong. There are several reasons for this. One of the main - and often underestimated - cause is: incorrect design combined with a lack of serious validation.

'The big problem is that micro-organisms are not visible to the naked eye. By the time you see them, you are too late'.

Open equipment, such as conveyor belts, are largely easy to check for visible contamination. A conveyor belt may seem easy to clean, but it is not. Especially not if there are rollers under the belt that support it. If the belt is sprayed clean at the top, the still dirty roller at the bottom makes the belt dirty again. Even visibly clean, such a roller can give the belt microbial post-contamination. Burggraaf & Partners uses the terms direct and indirect product contact surface for this purpose. The top of the belt comes into direct contact with the product and the roller below it indirectly. Both must be clean and, if necessary, disinfected for safe start-up.

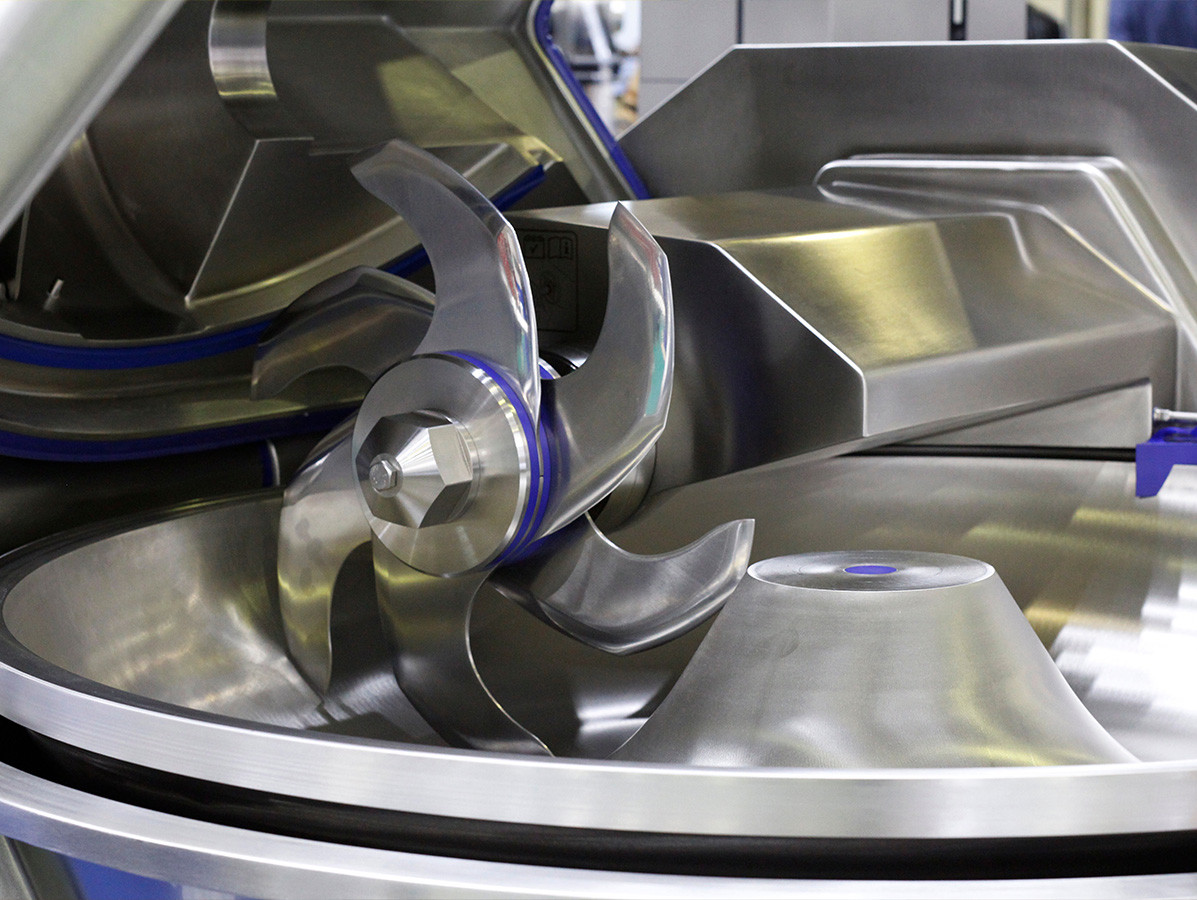

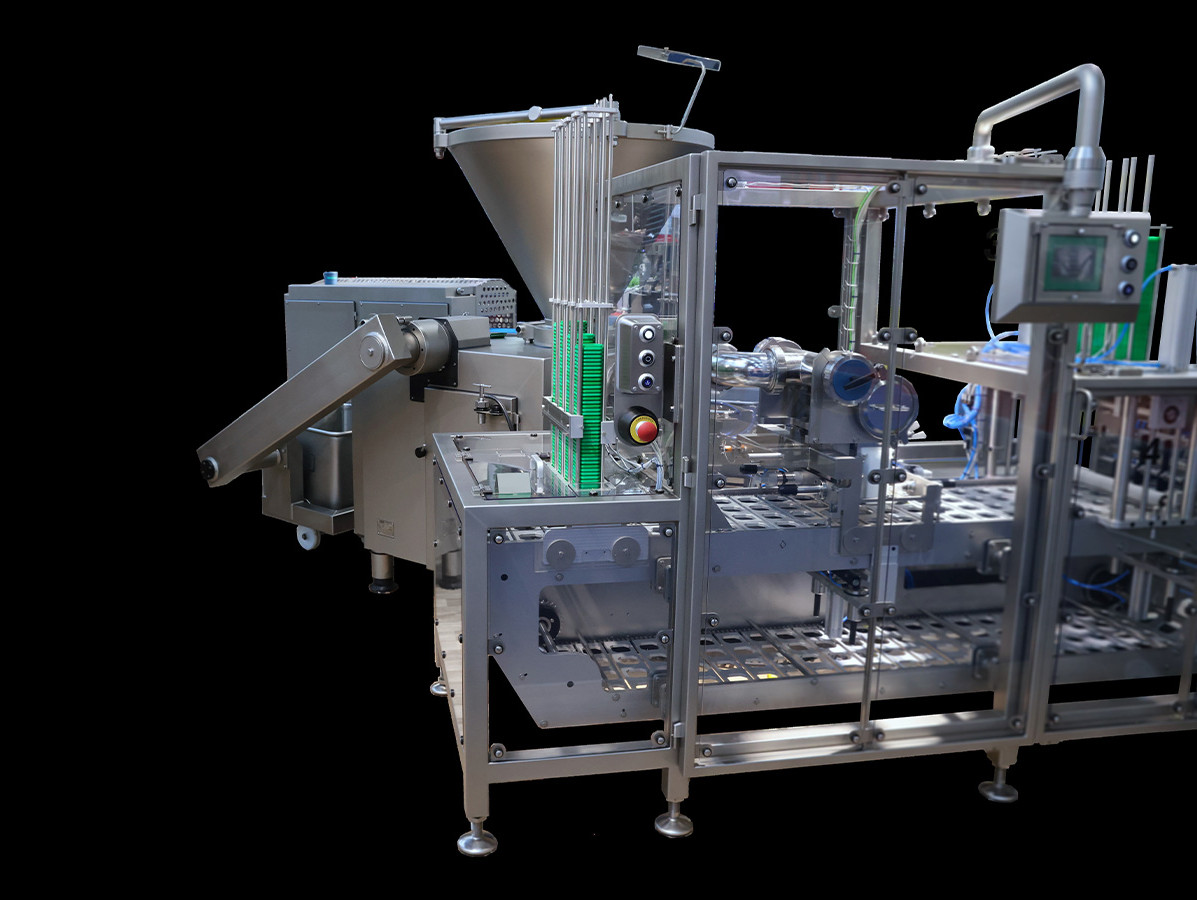

Things get trickier when closed equipment is involved, such as pumps, valves and measuring instruments in a pipeline. Only when dismantled is visual inspection possible. In practice, such a process is cleaned automatically (cleaning-in-place, CIP). Automatic cleaning has the advantage that the cleaning process can be validated and later verified. The European Hygienic Engineering & Design Group (EHEDG) has developed a test method in which such components are validated for cleanability down to the microbial level. The worst-case situation is a substantial contamination with a test micro-organism. This involves filling the entire component with a growth medium after cleaning to check whether and how many micro-organisms are left behind, compared with a reference tube. EHEDG then says that if an approved component is visually clean, it can also be assumed that the component is clean down to the microbial level. In other words, it is important that the plant later comes up with a worst-case scenario for the component, such as substantial contamination with the product to be produced. If this leaves product residues after cleaning, the CIP method may be insufficient, but the design may also not be suitable for the application with this particular product. This sometimes occurs for products with certain viscoelastic properties.

Following the results of EHEDG's test method, a number of design criteria were drawn up. These can of course be found in the 52 EHEDG guidelines (www.ehedg.org), but are also summarised in the EU standard NEN-EN 1672-2 Food processing machinery - General basic rules - Part 2: Hygiene requirements (www.nen.nl). The guidelines and standards do require explanations, and we provide these almost daily in all kinds of training and courses.

1. The underestimation of the machine builder

The machine has been built this way for years and the machine builder is not aware of complaints from the market. A contamination occurs visibly only when a certain bacteria is present, can grow and cannot be completely removed. Never a problem before - nor with other customers, only with this customer. The case is then not dealt with seriously.

A typical example we encountered some time ago was a stuffer; a meat pump from a well-known manufacturer. The pump is cleaned manually. The shaft seal consisted of a double lip seal. As the operator went in with his hand and a cloth to clean the shaft, he damaged the front lip. As a result, the cloth was partially squeezed into the space behind the first lip. The pump is then sprayed out, but obviously could not take all the dirt with it behind the first lip. Over time, a pathogen grew here, infecting the sausages. The design was modified at this meat processor. A few years later, we came across the same type of meat pump at another meat processor. There, the design had not yet been modified. This is obviously irresponsible of this manufacturer.

2. Failure to find the cause of a contamination

It also happens that the quality department sees an anomaly and starts an RCA. It finds occasional contamination, but not the cause yet. After three to six weeks, the problem simply disappears - and the books are closed. The fact that a leaking seal in a pump or a valve was the cause, and over time it stopped working, and was replaced in the workshop, is not communicated.

This is basically a design fault, as the machinery directive (CE) states that for equipment in the food industry, non-cleanable parts must be hermetically sealed so that no dirt can accumulate in them. This then also applies to failing seals. And NEN-EN 1672-2 prescribes a risk analysis. In case of failure, leakage must be immediately visible so that an operator can intervene in time - and not only after three to six weeks.

In both cases, it is important that a service or maintenance engineer is trained to involve the quality department if a component looks dirty or smells. The quality department can then take a sample and deploy aerobic and anaerobic to investigate whether there is a micro-organism in it.

EHEDG's design requirements and EN-1672-2 were issued for a reason. They are based on practical experience. It is good if both the quality and technical departments at a food manufacturer, as well as the machine builder, are aware of them. This prevents a lot of unnecessary post-contamination.

Courses on hygienic design:

Zoning and Building; listeria-free production 13 and 14 December 2022

Hygienic Design; in-depth 15, 16 and 22 December 2022

Hygienic engineering - Dry processes 20 December 2022

CIP - Innovative cleaning techniques 17 and 18 April 2023

burggraaf.cc

Source: Vakblad Voedingsindustrie 2022