Everyone knows that eating less salt, less saturated fat and less sugar is better for their health. If consumers were to opt in their masses for low-salt alternatives of processed food products it could result in 5% fewer heart attacks and 7% fewer strokes. So why is this still not happening on a large scale? We asked the industry.

For years, the World Health Organisation (WHO) has been warning of the health risks associated with eating too much salt, fat and sugar. In 2005, an EU platform was established ‘For Action on Diet, Physical Activity and Health’ and in the Netherlands a National Agreement to Improve Food Product Composition was reached in 2014 which contains sector-wide agreements on reducing salt, saturated fat and sugar in processed food products. This produced a few improvements such as a considerable reduction in the salt content of bread (21 percent), according to research by the National Institute for Public Health and the Environment (RIVM) in 2015. But far from all product categories have been improved. It turns out that cheese is just 11 percent less salty than in previous years, and that reduction does not even apply to every type of cheese. According to the research, meat products intended as sandwich fillings are still just as salty as in 2011 and 2013, and the same holds true for soup, while for saturated fats there are no clear differences in today’s levels compared with 2011.

Approximately 80 percent of the average person’s daily salt consumption comes from processed food. A study by Marieke Hendriksen (RIVM) last year revealed that halving the salt content in all processed food products could reduce the number of heart attacks by 30,000 and the number of strokes by 53,000 over the next 20 years. In view of the urgency to make the product offering healthier, the Netherlands has put the topic of food product improvement high up on the political agenda since it became president of the EU at the start of this year by introducing the ‘Roadmap for Action on Food Product Improvement’. This roadmap strives to achieve salt consumption of just 5 grams per person by 2025, representing a 30% reduction. In addition, healthier choices must be more easily available by 2020. The roadmap has been signed by 22 EU member states plus Norway and Switzerland as well as European food industry organisations such as FoodDrinkEurope and European health organisations.

‘Work from the same starting point and use the same measurement methods everywhere’

What do these goals mean for the Dutch food processing industry? Are they realistic and attainable? Betty Groen, Marketing Advisor at Dutch Spices, responds: “In terms of salt I definitely think that this ambition is attainable. But the roadmap doesn’t include any clear agreements about the reduction of saturated fats and sugar so it’s not possible to measure success in those areas.” Erik Vliek, Director of Technology & Production at Vaessen-Shoemaker, also thinks that a salt reduction of 30% is feasible and Tom van Zeeburg, Business Development Manager at AkzoNobel, and Walter Blom, New Business Director at Barentz Food & Nutrition, agree with him. So there’s no problem, is there?

Betty Groen: “Yes, it does sound very easy: the industry just has to reduce the salt level and that’s all there is to it. But we also want products that have a long shelf life and look appealing, and those are two important functions of salt. Plus we don’t want to make any compromises on flavour. In consumer panels, low-salt products are rated as less tasty. Nevertheless, it’s possible to reduce salt, as demonstrated by the fact that bread has become less salty over the past few years. Consumers have had time to get used to it gradually. The same goes for the reduction of salt in pre-seasoned products such as potato wedges. Statistics from the research agency Nielsen show that the volume of retail sales of salt has remained virtually the same, which can mean that people aren’t buying extra salt to add to processed food products. That’s an encouraging insight.

Erik Vliek (Vaessen-Schoemaker): “Simply eliminating salt from products can pose a threat to food safety, and replacing fat can change the mouth-feel, taste and texture of a product. Substituting ingredients, for example by using carbohydrates or sugars instead of fat, can create a new problem such as higher calories in the end product. It is possible to slightly reduce salt without it being noticed, but for anything more than that it’s necessary to find alternatives to compensate for the loss of flavour.” There are plenty of alternatives: salt can be replaced by spices such as nutmeg, paprika or pepper or by mixed herbs. There are also other ways of extending the shelf life, such as by using natural preservatives and antioxidants like rosemary. Vliek: “We’ve achieved good results with this in fish products.”

The other option is to adapt the sodium-potassium ratio in table salt. OneGrain by AkzoNobel and Nu-Tek Salt (distributed by Barentz) are good examples of this. OneGrain contains 50 percent less sodium but the flavour remains unchanged thanks to the addition of a natural aroma to the grain. Meanwhile Nu-Tek Salt, which originated in the USA, is based on potassium chloride, with the bitter taste being eliminated via a patented process. Tom van Zeeburg: “Manufacturers can switch to a modified type of salt overnight, so that doesn’t need to be an obstacle to salt reduction in the food industry.”

Besides flavour, the cost factor also plays an important role in manufacturers’ and consumers’ decisions about whether to produce and buy reduced-salt products. Walter Blom (Barentz Food & Nutrition): “Apart from water and air, salt is the cheapest ingredient in a product. Any substitute will always cost more money. Without clear legislation, not many manufacturers will be prepared to pass these costs on.”

Tom van Zeeburg (AkzoNobel) echoes this: “Retailers are under the impression that consumers are unwilling to pay a slightly higher price for the same product. We disagree. In the case of bread, for example, it means a difference of just one cent per loaf.”

In spite of all this, companies are regularly asked to develop reduced-salt products. Erik Vliek: “The number of requests for reduced sugar is starting to rise too.” Dutch Spices has also noticed this, and the company faces an extra challenge because it produces entirely allergen-free. But even then, there are options: “A cajun herb can compensate for the initial sweetness,” says Betty Groen.

Furthermore, each country or region has its own flavour preferences. Vliek: “In Western Europe the trend is to reduce the salt and fat content. The UK has been leading the way in terms of sodium reduction for years, whereas in Germany they are sticking to a full, fatty flavour. There’s not much point in adapting the Dutch products as long as there are foreign imports of products that are higher in fat and salt.”

‘We call for clear labelling’

Therefore, the manufacturers applaud the harmonisation of the standards for food product improvement in all affiliated countries. Tom van Zeeburg: “If agreements are based on guidelines, manufacturers are still reluctant to commit to them. Legislation can be a good solution in this case.” Walter Blom: “Legislation is better because right now there is no level playing field.” Erik Vliek adds: “It’s important that everyone works from the same starting point and uses the same measurement methods.” “Regulations force suppliers, manufacturers and retailers to work together to achieve the goal on behalf of the whole chain,” comments Betty Groen.

Needless to say, this discussion also includes a role for the consumers who ultimately decide whether to buy a product or not. Betty Groen: “Awareness and availability are important. It would be nice if, at least for the essential products, two versions could be displayed side by side – the regular version and a modified one. At the moment the offering is largely made up of regular versions.”

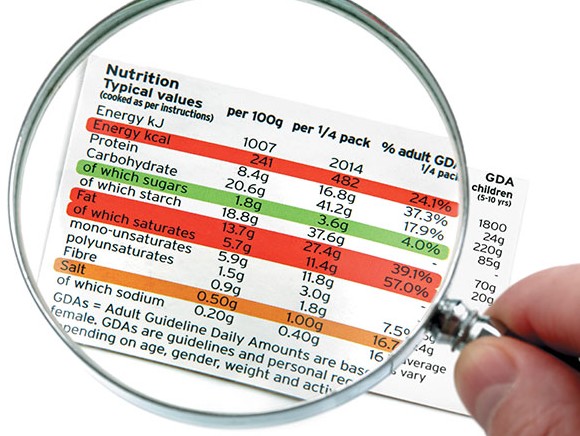

“Many consumers lack food knowledge,” says Erik Vliek. “Children are having to relearn where their food comes from at school because they no longer know. Without the right knowledge, consumers can easily make the wrong choices and they will end up eating an unbalanced diet or too much of certain substances, such as sodium.” That’s why Tom van Zeeburg calls for clear labelling which makes it easy to see how much salt a product contains. Walter Blom states: “As consumers become more aware of their salt intake, they can also exert increasing influence on the market by demanding reduced-salt products.”

Source: Foto boter: ©iStock.com/vikif,Foto suiker: ©iStock.com/Okea, Foto label: ©Brian A Jackson/Shutterstock.com, Foto kok: ©Wavebreakmedia/Shutterstock.com