While politicians and scientists tumble over each other in the search for the best solutions to the global climate problem, there is a striking consensus when it comes to the indoor climate in production areas. In particular, there is agreement on its importance for ensuring (food) safety. But what is the optimal indoor climate for a production area? And how do you achieve it?

Food production often takes place in a refrigerated environment. Humidity is usually high. The resulting problems are numerous. Moisture in the air increases the rate of corrosion, resistance values of insulation decrease, oxidation of electronics increases failure of electronic components, and pneumatic conveyances are disrupted. Food safety risks arise because mold and bacteria grow faster in a humid environment. An obvious statement? Perhaps. But why do things still go wrong so often? We discuss causes, consequences and the solutions with two experts, both having more than 30 years of experience in the industry: André van Zutphen, expert sales engineer at Munters (supplier of energy-efficient air treatment and climate solutions) and Ray Denessen of DenDoor-GTS (supplier and partner in industrial doors, particularly for the food production and processing industry).

It is a major pitfall in ensuring food safety: humid rooms with a lot of condensation and frosting, André and Ray agree. "The ideal relative humidity (RH) is at 60%. When the RH is higher, air absorbs less moisture," André begins. "Drying after cleaning is therefore slower and condensation occurs on ceilings and cold surfaces. As long as there is water, transport of bacteria is possible. You'll get mold on sealants, and you'll get bacteria that become resistant to cleaning agents. Surfaces that never get completely dry are never really clean." To ensure dehumidification, extractors and fans are often used in the food industry. "But with every cubic meter of air drawn in, there is also moisture sucked in," he continues, "because, in absolute terms, the outdoor air often contains more moisture than the indoor air. So always start by reducing intended and unintended ventilation to a minimum. Make sure your building is sealed as much as possible."

Ray, as a door specialist, can only agree. He explains: "A freezer works like a sponge; as soon as a door opens, the cold room sucks in any moist air that is there. Therefore, an improper arrangement, poorly closing or very slow doors, and doors that are left open for long periods of time cause many problems. An evaporator in a cold room can do two things: maintain the temperature and dehumidify. But it cannot do both at the same time! A poorly closed freezer or refrigeration room continuously requires temperature regulation, which prevents the installation from dehumidifying. The excess moisture in the air settles on all cold surfaces. The result: snow-covered cold rooms, frost growth and condensation on ceilings, ice formation on (cardboard) packaging and dripping condensation on products. All of which are of no benefit to food safety."

"Refrigeration as a dehumidification technique however is often used in the food industry because there are already cooling systems in place," André said. "With this technique, you refrigerate air until the moisture can no longer be absorbed. We refer to that temperature as the dew point. When air cools down to below the dew point, water condenses. That water enters your cooler, and that allows you to drain it. However, the technique is not that effective, the capacity is limited. In fact, the difference between the outgoing and incoming airflow in terms of absolute moisture content is very small. In addition, the air blowing out of the system is cold. Therefore you make surfaces even colder, which in turn causes condensation. The other day I visited a chicken slaughterhouse during the cleaning process. Immediately after cleaning the ceiling dried up very nicely. Until the cooling system was turned on again... As the ceiling got cold and the temperature dropped below the dew point, condensation appeared. Within no time, machine parts and surfaces were soaking wet again."

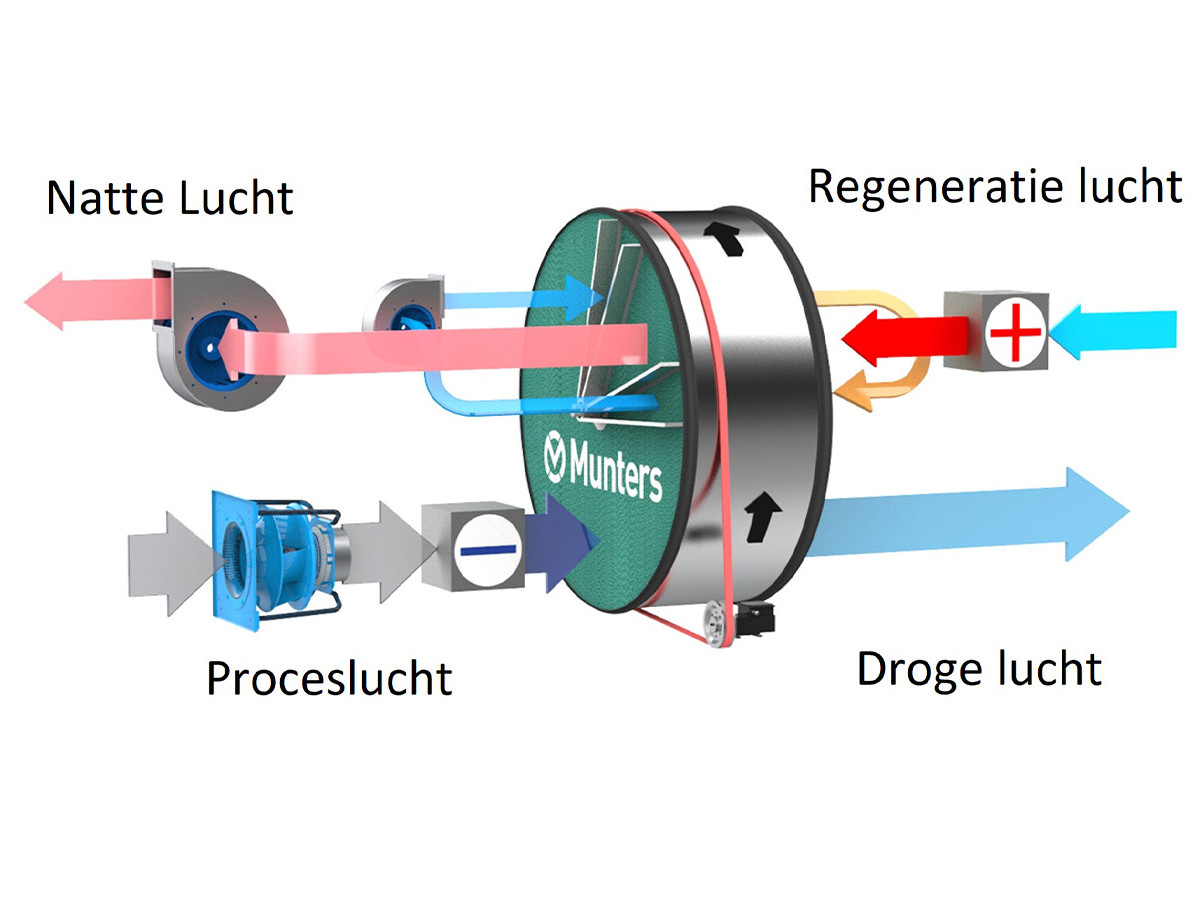

Another drying technique also exists: absorption drying. How does that work?

André: "Absorption drying was invented by our founder Carl Munters. The technology consists of a rotating molecular filter, the so-called drying wheel. It filters water vapor out of the air. That moisture is released to a drying agent inside the wheel, which has two streams of air passing through it; the main stream dries the air, a counter-current stream blows the moisture out. The air blown back into the production area is drier and slightly warmer. This does not pose a problem during production. Normally, 30% of the refrigeration plant's energy goes to dehumidification. Adding absorption drying allows all the energy to go to cooling. Instead, it is more likely that there will be overcapacity."

Let's go back to that other condition: as little ventilation as possible. Ray: "During the day, doors are constantly opening and closing. So there is always moisture coming in, there are always temperature differences, so there is a risk of condensation and, in freezers, ice formation. When looking for a solution, it is important to realize that every situation is different. There is no standard door for a freezer or refrigeration application. Some customers have loading docks at the front, which means you would have more moisture air entry. Others have conditioned areas that already trap a lot of moisture." What he often notices in practice is that the layout isn't always optimal: "A cold store ten meters removed from a platform with overhead doors that constantly open and close; that's asking for trouble. We can make improvements in such a situation by installing conditioned locks, for example, but of course there has to be room for that. And it must fit in with the customer's logistics. Fortunately, architects are increasingly involving us in projects as early as the development phase."

André: "Sometimes the solutions are quite simple. A freezer cell, for example, always has the same temperature zones. At night, when the doors remain closed, we dry the air until the ice sublimates; it then goes directly into vapor form. In the morning, everything is dry again. In refrigeration, the situation is different. Production areas are cleaned more often; the products processed there contain more moisture for one customer, while for another they contain less; there is more ventilation because people are working there as well; doors open and close more often. All of that has to be mapped out on a situational basis."

Ray agrees: "There are no standard solutions; you have to take dozens of factors into account. Therefore, the most important thing is the contact between supplier and customer. It's always tailor-made."

Name some of those factors you need to consider?

"Is the front room conditioned or not? What is the temperature in the front room and what temperature are you measuring in the freezer, in other words, what is the Delta T? Is the operation 24/7, or only during the day?" lists Ray. "How many logistical movements does the door make per hour? What space do you have to build the door into? Is there another existing door they want to keep in use, as an emergency door? If hygiene is essential, the whole frame has to be made of stainless steel or anodized aluminum; also the internal work has to be foodsafe. In that case, you don't want brushes in the side frames; these make one large lair for bacteria and dirt. The doors should not drip moisture during fast opening. After all, people also walk underneath them carrying raw materials or finished products in open bins. You should therefore drain the capture of any condensation to the side. It is also better for hygiene if personnel do not have to touch a button to open a door. A major problem is that doors sometimes have long opening times. There are companies where the door barely has a chance to close due to busy logistics. Or staff presses the door's stop button so it remains open. I get it; it's much easier than having to wait on that door every time and the stress on the production floor is high, they have to meet their targets. But it's not the right approach; it's a source of frost and condensation. In such cases, an air curtain might be a better solution. Or, of course, a more rapid door and the entire system should be automated so that 'leaving it open' is not manipulable."

Many requirements can be found in HACCP guidelines. So why do things still often go wrong in reality?

"Clients in the food industry are initially very much guided by the regulations and guidelines," says Ray. "Until they receive quotations that fully comply with them. Then they start saving money. A door containing only stainless steel vision parts costs less than a door in which all parts, including the transmission, control box, winding shafts, layers, etc., are made of stainless steel. If you need ten doors, of course, that adds up. But be careful what you decide on. Before you know it, the rusting hassles begin and brown water trickles down your door and side rails. Regular and professional maintenance is also often skipped, unfortunately. One result is that essential sealing rubbers, for example, no longer provide the necessary seal due to wear and tear."

Summing up: what are the positive effects if you manage to reduce ventilation with tightly closing doors, and create drier air?

André: "Corrosion and mold formation stop. Bacteria thrive worse at low humidity levels because cell walls don't cope well with rapid changes in humidity. Cleaning is proven to be more effective with drier air and dry surfaces. Ray: "The rooms also become safer. Frost and condensation disappear, so no more puddles and slippery floors in the freezing aisles."

"In addition, it creates a better working environment for staff," André concludes. "A dry cold room or freezer feels more like a sunny cold winter day instead of that wet-cold."

We've had enough of "water cold" and wetness on our hands this spring. We crave drier air; inside and out. So fling those doors open! Or shouldn't we?

Main photo: ©FOTOGRIN/shutterstock.com

Source: Vakblad Voedingsindustrie 2023