Big data, smart industry, IoT, cloud robotics, virtual and augmented reality – none of this is science fiction any more. Aiming to keep it all as simple as possible, this article ‘merely’ explores the trends and developments: when it comes to robotisation and automation, where do the opportunities and challenges lie? Four experts share their views.

At the end of last year, researchers from the Netherlands Scientific Council for Government Policy (WRR) published a report called De robot de baas – De toekomst van werk in het Tweede Machinetijdperk(‘Mastering the Robot – The Future of Work in the Second Machine Age’). In their introduction, the researchers state: ‘To take advantage of new opportunities and offset any real or potential disadvantages, politicians and the public must take action’. What strikes them is the limited use of robotisation so far: ‘Employers consider robots to be too costly,’ they conclude. ‘They require a different revenue model and experience technical problems. Plus there are cultural issues – people don’t want them’.

Less than a year after publication of that report, food industry experts are unanimous in their belief that smart industry and robotisation have grown tremendously over the past year. Ben Prins is a management consultant at PMC and, as Smart Industry Ambassador, is focused not only on industry but also on higher education. “It’s no longer just the major industrial companies that are getting involved; SMEs are joining in too. They’re curious. Seminars and workshops are being organised specifically for SMEs, such as by Rabobank, to give them guidance.” Peter Kiekens (Marketing Manager Benelux at Fanuc) shares the sense that the robotisation market in Western Europe is exploding rather than lagging behind, especially among the larger players. “People were maybe a little cautious five years ago, but they’re not any more.” Meanwhile, the Markets and Markets research agency predicts that the market for industrial robots will see accumulated annual growth of 11.92% between 2016 and 2022. According to forecasts, the market will be worth around 79.58 billion dollars by 2020.

And yet: just because it’s possible in theory doesn’t always mean that it will (soon) become reality on a large scale. There are numerous constraints, according to WRR: ‘The technical opportunities are more limited than people think; there is still a lack of investment in robotics; the utilisation costs are too high’. Ben Prins adds that the greying population also plays a role. “But that will change; the new generation is growing up in a digital world and finds ‘connecting people, machines and systems’ completely normal. They are open for innovation. Nevertheless, a lot more money could and should be invested in robotics. A lack of awareness plays a big part, especially among small and medium-sized enterprises. One answer to this could be better information from both the government and robot suppliers. And of course education has a lot of influence. The new generation will have to take the lead.”

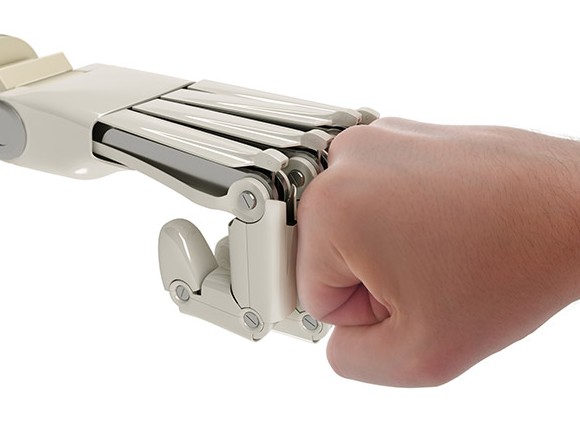

In WRR’s ‘Mastering the Robot’ report, ‘complementarity’ is called a key concept: having people and robotics work together and grow more productive as a result, instead of letting robots take over people’s jobs. And that is precisely what the temporary employment agency HOBIJ is doing with its Robots@work project. In the spring of this year, it became the Netherlands’ first temping agency to supply not only people but also robots. “You create the optimum when people and robots collaborate,” says Paul van Dieperbeek, Team Leader Sales at HOBIJ. “Our customers hire a team from us, and that team is increasingly made up of people plus robots. We supply the trained operators, service and maintenance, and our partner programs the robots. Hiring a robot is based on the same principles as hiring a temp; if you want to terminate their employment, you simply give notice on the contract. Thanks to the use of advanced sensor technology, our ‘intelligent robots’ are aware of their surroundings. The robots are affordable, easy to configure/reconfigure, safe to operate, easy to move and can be used in all kinds of locations. A robot can be especially beneficial in cases of repetitive or physically demanding work with a high level of absence due to illness. Potential activities include order picking, assembly line work, machine tending, packing and palletising.”

HOBIJ is introducing this new form of flexible automation to the industry through its ‘human vs. robot’ campaign. It dispels numerous reasons for not taking the plunge: “Companies don’t run any major risks; they don’t need to take extra safety measures or adapt their production lines. We deployed the first robot arm along with a team of operators in April and it’s already become clear that there are significant benefits for companies. The robots can be used 24/7 and are ideal for boring, repetitive work. They never fall ill and deliver consistency in terms of both quality and quantity.”

Fanuc is a global player and market leader in industrial automation. In the eyes of Peter Kiekens (Marketing Manager Benelux), there are few limitations. He explains about the latest addition – a new collaborative robot, or ‘cobot’ – with enthusiasm. “This robot doesn’t need a shield around it; it does its work in amongst the employees. The ‘co-’ also stands for ‘colleague’, because this robot supports the humans. So far, it’s only being used for secondary food-processing activities, such as packing and handling.” There are also some constraints: cobots must legally comply with a maximum speed limit because they work in close proximity to people. If they go too fast, that could pose a danger to humans in which case they must be separated off. “By the way, they’re not always better for high-speed picking of food items,” clarifies Peter. “Robots can accelerate tremendously quickly, but if a robot arm grabs brittle cookies too quickly you’ll be left with nothing but crumbs, and fruit can become bruised. Increasing the speed is only relevant when the food product can also cope with faster handling.”

Investment capital for innovation

In the years ahead, the global robotics industry can apply to a new investment fund to obtain essential capital. The private equity firm Chrysalix Venture Capital in partnership with Robo-Valley (TU Delft) have announced that they are prepared to invest EUR100 million through the fund. According to the initiators, the development of new technology often runs aground at universities and in laboratories that lack the necessary capital to grow and take their innovations to market.

In WRR’s ‘Mastering the Robot’ report, Anna Solomons (Utrecht University) claims that new technology only improves productivity if organisational changes are also made to help people cope with the new situation, such as more training opportunities and more autonomy in their work (‘ownership’). That latter point is nothing new; over the past decade, more and more manufacturing companies, including in the food industry, have introduced the Total Productive Maintenance (TPM) philosophy. TPM is a methodology for improving the availability of machines and systems, based on the idea that operators should feel responsible for the machine park. If they regard themselves as owner of ‘their’ line, they will take better care of it. Small multidisciplinary teams gradually improve the overall equipment effectiveness (OEE) of their machines. In order to achieve that, attention is given to autonomous maintenance, preventive maintenance, training, safety and standardisation of operational processes.

Maartje Mikx from technical training firm ROVC has noticed signs of a shift in the need for training among the food industry’s major players over the past year: “Previously we trained most technical operators to MBO level 2 so that they could perform minor maintenance tasks themselves. But as the machines and the automation become increasingly complex, the tasks are changing. It’s about more than just periodic greasing and minor repairs. Now, they have to be able to fix complex breakdowns, to have far-reaching knowledge of sensors and to be able to program systems. So over the past year we’ve noticed more and more technical operators being trained to level 3 or even 4. That also requires a higher level of abstraction, which not all operators have in them.”

When implementing robots, the management should focus closely on what happens on the work floor. “The manager needs to be a good coach and stimulate the employees to tackle their own problems themselves. At the same time, the maintenance department must facilitate the technical operator’s autonomy by learning to let go of certain tasks. We regularly see cases of the maintenance department being too quick to jump in to help an operator: ‘Leave it, we’ll do it, you don’t know how to’. That’s why we also run courses for maintenance departments to teach them how to provide support and guidance to a technical operator or junior mechanic. By helping out during practicum training programmes they can fine-tune their supervision skills. This lets them discover for themselves that better-qualified operators really do have added value. I expect the less high-profile companies to follow this trend; in five years’ time there will be hardly any work for MBO 2-level operators in Dutch factories any more.”

“In practice, the food industry is constantly under price pressure,” says Paul van Dieperbeek. “Companies are fervently looking for smart solutions to reduce their costs. And yet they don’t immediately think of investing in robotics.” Ben Prins thinks that this is due to a lack of foresight. “SMEs don’t usually have a clear vision of where they want to be in five or ten years’ time. There are few exceptions, but they often don’t have a long-term view. Lack of knowledge of – and lack of familiarity with – robotisation also plays a role. I often hear managers say: ‘That won’t work for us’. Yet if they used just one or two robots for part of the production process they would be able to produce much more quickly and efficiently. These are just the kinds of companies that stand to benefit from HOBIJ’s flexible automation.”

Maartje Mikx (ROVC): “To reduce your company’s costs it makes sense to first decide what you want your people to be able to do, then to look at their current level of competence and finally to focus on the gap between the two. You don’t always have to invest in a complete MBO course; a brief spell of extra training can often be enough. The company Duyvis in Zaandam, for example, recently automated a substantial part of its activities and invested in new machines. There, we first drew up job profiles for the colleagues in the maintenance department and then ran knowledge tests. The men were then enrolled for courses with Opennetwerk individually, i.e. they only learnt what they needed. Right now we’re running an in-company programme for the mechanics.”

Peter Kiekens (Fanuc) does not expect to see any truly revolutionary changes in the next five years, but he does predict significant technological evolutions. “It’s about improvements in gripper technology, vision technology, orientation and positioning. The focus is shifting to configuring robots more easily. Soon, they really will be multi-purpose. Furthermore, they will be made more suitable for the primary food-industry processes, in terms of their coatings and materials being designed to withstand the cleaning agents that are used. The focus is on durability and sustainability: robots will have fewer defects and be more energy-efficient.”

“Robotisation will play a crucial role in the factory of the future,” states Ben. “Software developers are continuously working to find solutions that will enable humans and robots to work together effectively. So much is already possible, but if we’re to continue to progress it’s essential that we have more qualified specialists. Things are moving in the right direction. At TU Delft, in the so-called Robo-Valley, 170 scientists are currently working with the government on next-generation robotics. A total of 21 robotics start-ups are based there alongside existing companies.”

“The areas of application are expanding rapidly,” says Paul Dieperbeek (HOBIJ). “New gadgets and opportunities are emerging every month. That makes it difficult to predict what will be possible in five years’ time. Some people see the disappearance of jobs due to extensive robotisation as a threat. That was the same for our business model. We’ve tried to turn that threat into an opportunity. It might seem like cannibalism; the use of a robot has led to the loss of some jobs for us too. On the other hand, new jobs have been created. We train our people to cooperate with, maintain and if necessary configure the robots on site. We think that robots can actually help us to retain companies, and hence jobs, in the Netherlands. Once people and robots really start to collaborate...that will mark the start of a new era.”

Source: Foto robothand: ©maxuser/shutterstock.com, Foto data: ©vectorfusionart/shutterstock.com, Foto studenten: ©ROVC