As part of the war on food fraud, it has recently become mandatory for companies to perform a Food Fraud Vulnerability Assessment to check how well protected they are against food fraud. Forming part of quality systems such as FSSC 22000, BRC and IFS, this assessment is far from discretionary. There’s no way around it; each and every food processing company must investigate how vulnerable it is.

Food fraud is a crime, and the people who commit it are criminals. ‘Think like a criminal to fight food fraud’ is the headline on the brochure for the Food Fraud Vulnerability Assessment Tool (which is available for free download). The tool has been developed by SSAFE and helps companies to focus on food fraud risks. Wageningen University, RIKILT Wageningen UR and VU Amsterdam have provided the scientific basis for the tool. Aldo Rus, Business Unit Manager at KTBA FoodCampus, has 25 years of experience in the food industry and quality assurance. For KTBA FoodCampus, he developed the Food Fraud Masterclass. “Food fraud is estimated to cause between 30 to 40 billion dollars’ worth of damage to the global food industry each year. It’s impossible to give an exact figure because only a fraction of all cases of fraud are actually discovered.”

Food fraud not only costs companies a lot of money, but it also damages consumer confidence in food products – which is logical, because if expensive ingredients are being substituted for cheaper ones, it means that they are paying over the odds. Food fraud can also lead to health risks, e.g. because of a lack of clarity about the origin of the product or because a product becomes contaminated with one or more allergens. Most of the food fraud incidents in the Netherlands that are listed in the RASFF database or covered in the media involve meat (or meat products), fish (or fish products), animal feed or eggs. The fraud is primarily related to incidences of addition, dilution or substitution with cheaper product material, and to fraudulent declarations about the production (management) system or the production process.* The Dutch Consumer Association has also conducted research into food fraud. In 2015-2016 it selected over 150 products from product groups in which authenticity problems are known to occur. 33 products (21%) of the 156 products tested were found to have deviations. The results of the study were published in October 2016.

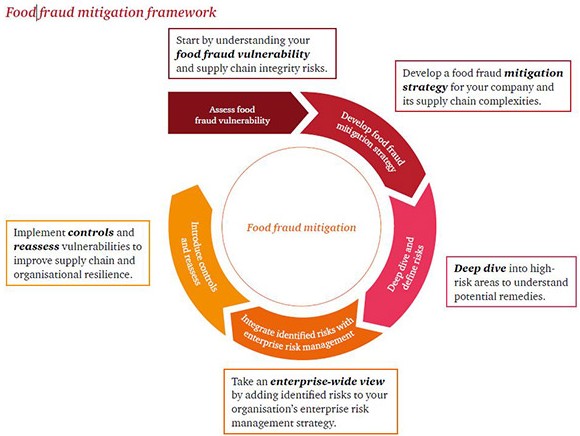

After the high-profile horse meat affair, the Dutch government and the private sector set up the Task Force Food Confidence in 2013 aimed at rebuilding and increasing consumer trust in food. In 2014, the Ministry of Economic Affairs commissioned LEI Wageningen UR and RIKILT Wageningen UR to perform a quick scan of food fraud in the Netherlands in the context of ‘Safe and responsible food’*. The researchers concluded that there was little to no knowledge about food fraud risk factors, the suitability of (analytical) methods for detecting various types of food fraud in various products or product groups, the legal enforcement framework or a risk-based control system specifically aimed at food fraud. On 29 January 2015 the task force finished its work. In the final report, it emphasised the need to improve food integrity by using international quality systems such as FSSC 22000, BRC and IFS. “And that has since happened,” comments Aldo Rus. “A Food Fraud Vulnerability Assessment has formed part of a number of food safety standards, such as BRC, since July 2016. You have to conduct the assessment, otherwise you won’t achieve the standard. So the Global Food Safety Initiative (GFSI) is forcing companies to comply.”

“A decision tree and 50 questions enable food companies to check their own vulnerability and that of their suppliers,” explains Aldo. “The analysis places considerable importance on fraudster profiles and the financial position of the suppliers. The questions highlight where the risks lie; it’s then up to you whether you decide to take action. Tackling food fraud calls for a different way of thinking, such as by paying more attention to the role of purchasers. If a raw material is offered at below the regular price, that should set alarm bells ringing in their minds – can it be legitimate if it’s so cheap? The tool can help to provide insight into where and when you need to intervene, but it doesn’t tell you how big the risk should be before you decide to take action. We can help companies to make those choices.”

“In the past the main focus was on hygiene and food safety: HACCP,” continues Aldo. “Now that tackling food fraud has become anchored in the quality system, it will also receive more attention. Food manufacturing companies used to source their materials based on the specifications; there were no fundamental controls of whether the specifications were being adhered to. Formally speaking, from a traceability perspective you’re required to monitor your product one step upstream and one step downstream in the supply chain. In the years ahead, it will become important to achieve transparency in the whole chain.

‘A Food Fraud Vulnerability Assessment forms part of a number of food safety standards’

There is a trend towards shorter chains because the fewer links there are, the less risk there is of things being tampered with. The coffee producer will work directly with the plantation, installing a shipping container that is filled and sealed on site and then shipped to the Netherlands to guarantee that the Arabica beans can’t be blended with inferior ones. In the past, nutmeg used to be sourced in pre-ground form, but that left the powder open to being mixed. That’s why, just like peppercorns, nutmeg is only purchased whole nowadays. That makes it much easier for you to check that what you’re buying is pure.”

“All enforcement used to be done by the government, but now that companies have to shoulder their own responsibilities they will conduct their own (announced and unannounced) checks on each other more often too. Retailers already do that with their suppliers. They add clauses to their contracts along the lines of ‘If you want to supply to us, then you have to accept that we can show up unannounced to audit you’. The mere fact that you might be audited will reduce the fraud level; after all, there’s a greater chance of being caught. We’ll soon see companies auditing each other throughout the entire chain.”

“Besides that, more and more new (analytical) methods are being developed to detect food fraud. This will make it easier and cheaper to conduct random checks on raw materials and products. For example, Wageningen University has developed a way of analysing egg yolk to determine whether the egg is organic or not. I expect lab capacities to increase.”

“The cultural transformation that is needed won’t happen overnight,” adds Aldo. “Some people are quick to embrace change and set to work immediately, while others take a wait-and-see approach. But if you look at HACCP and what we’re doing now compared with 15 years ago…there’s been huge progress. I expect the same kind of thing to happen in tackling food fraud.” One thing is clear: ever-tighter demands are being placed in terms of assessing vulnerability and taking steps to prevent food fraud – but what does that mean for your own organisation? To help you find out, KTBA FoodCampus runs a Food Fraud Masterclass which explores the practical consequences of these demands and methods. “Slowly but surely, the industry will gain better control of things,” predicts Aldo. “How far should companies go in this? Well, I think we have to use our common sense: where are the biggest risks and where is fraud most likely? We’ll probably never manage to banish it completely; food fraud is an age-old problem.”

* Van Wagenberg, C.P.A., J. Benninga, S.M. van Ruth, 2015. Quick scan of food fraud in the Netherlands; who gathers which data? What research is available? What are the figures? Where are potential gaps in knowledge? Wageningen, LEI Wageningen UR (University & Research Centre)

Source: Foto haken: ©Your Design/Shutterstock.com