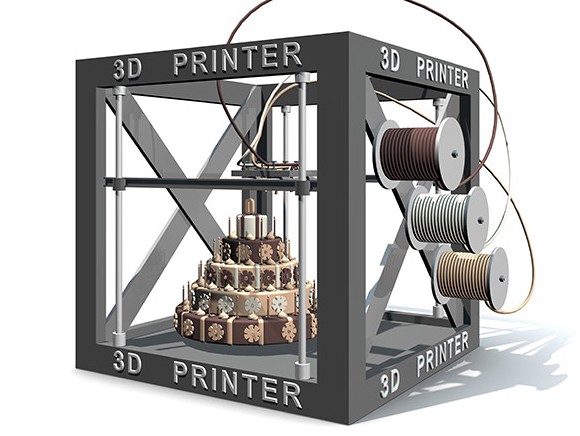

What will we be eating in 30 years from now? And how will our food be produced? During the 3D Food Printing Conference, which formed part of the Innovative Food-Agri Event in Venlo, the Netherlands, researchers and entrepreneurs examined the opportunities, developments and challenges of this novel technique from several different perspectives.

The first 3D printers emerged around 11 years ago, and there has been non-stop innovation ever since. Some start-ups have been busy launching printers for bakeries and restaurants, while others are aiming at large-scale manufacturing. At the 3D Food Printing Conference, Frits Hoff, CEO of 3D Innovationcenter , talked about one of the first versions, called Doodle #D: “The printer, which was originally developed for children, is really easy to operate via a laptop. Its first printing material was Nutella. The printer was demonstrated for the first time at a trade show in Rome in 2014 where it was a huge hit. Dutch supermarket chain Albert Heijn later used it in a pilot project in which shoppers could print a personalised topping on a cake on the spot. People were queuing up to use it!” But some prototypes never achieved a market breakthrough, such as the ‘Chef Jet’. Hoff: “There’s no question that the products it printed looked fantastic, but it was mainly just sugar – in other words, unhealthy – and it didn’t even taste nice.”

The 3D printers that have made it onto the market are mainly used by chocolatiers and bakeries to produce unique bonbons and cakes. In high-end restaurants, innovative chefs are experimenting with shapes and flavours. At the London restaurant FoodInk, for example, they 3D-print almost everything – from the food to the furniture. The food is produced using a 3D printer developed by ByFlow, a Dutch company. Just like the bakeries, the chefs primarily utilise the 3D printers to create unique desserts, often involving chocolate, but the technique is also increasingly being used for boring, repetitive tasks such as making ‘olive caviar’.

A common thread running through almost all the presentations given during the conference was how difficult it is to get the printing material right. “The first chocolate used in the printers didn’t taste nice,” said Frits Hoff. “Since then we’ve developed a good mixture, thanks to our partnership with Callebaut. This chocolate is able to withstand the heat generated in the printing process, has the right ‘bite’, doesn’t contain too much sugar and has an attractive shine.”

For Kjeld van Bommel, a researcher at TNO, the main focus is on creating different textures. “We’re exploring what it takes to print a juicy product, a crispy one or to create a cake-like texture, for example.” He displayed a range of prototype samples with various degrees of solidity and bite. “Another thing we’re working on is how a product is affected by subsequent processes such as oven-baking, freeze-drying, deep-frying or steaming. The product must still retain its shape after cooking. We want to know precisely what each phase does to the texture of the basic product. Does it become crunchy or soggy? And when does the product become too hard or too soft?”

Alan Kelly, a professor at University College Cork in the Republic of Ireland, has also been investigating ways to improve the printing material. Laughingly, he admitted: “We didn’t know anything at first, so we’ve definitely reinvented a few wheels in our quest to explore the opportunities of 3D printing.” What kick-started the research was a request from an Irish cheese manufacturer: ‘Can our cheese be used in 3D printing?’ That question resulted in close collaboration between a group of inquisitive food scientists and innovative machine builders. “We had no frame of reference so we just started experimenting based on good old-fashioned trial and error,” said Kelly. “We soon discovered that you can’t print with mozzarella – it’s too stringy. But what could be used instead? After various printer prototypes, nozzles that kept getting blocked and all kinds of printing materials, we eventually developed both a machine and a product that seem to work. We ultimately concluded that the structure of processed cheese changes under the influence of the heat and the stretching involved in 3D printing. Generally speaking that produced softer textures due to the weaker structures. 3D food printing changes the functionality and texture of dairy products. More studies are needed to better understand this process and identify possible applications.”

Johannes Heringlehner from the German Institute for Food Technology touched on the fact that most food products are made up of multiple components. “It’s almost impossible to make stable complex structures using today’s 3D food printers. However, it can be done using parallel multi-head printing, plus that would considerably speed up the printing process too.” His team is working to design such a printer. But Heringlehner was keen to point out: “The basis must be good too; the top priority is to find stable textures such as emulsions, foams and micro-suspensions.”

Chocolate, spreads, cheese, vegetable puree, meat – anything that can be sufficiently liquefied and subsequently solidify again is being trialled with the printers as an emulsion. Domenico Azzollini, a researcher at Wageningen University and Research (Food Quality and Design Group), explained the opportunities and challenges associated with edible insects in 3D food printing. “The use of insects in 3D-printed food offers a lot of potential,” he claimed. “In the Western world people are still averse to the idea of eating insects whole. When mealworms were included as a recognisable ingredient in cakes, people felt that they were eating rotting food.” And, according to him, insect burgers won’t catch on either: “If the food product doesn’t live up to people’s expectations of flavour and bite, most of them will reject it. But it could be accepted as a 3D-printed product with a completely new texture, bite and taste. After all, there’s no pre-existing sensory expectation.” Making fresh insects suitable for 3D printing entails first drying them, then grinding them into a powder and subsequently mixing them with another printing material such as icing sugar, mashed potato or wheat meal. “Adding insect powder creates a new, enhanced product with a higher nutritional value than the original product. But there are plenty of challenges still to overcome, such as improving the efficiency of functional fractioning.”

European regulations have been in place governing the launch of ‘novel foods’ since 1997, and companies must conduct a safety assessment and obtain authorisation in order to be allowed to sell such products in Europe. All products that were not available on the European market before 15 May 1997 are subject to the Novel Food Regulation. The term ‘novel food’ applies to newly developed, innovative foodstuffs, such as ones that contain additives to enhance the product’s health value. Novel foods can also be products made using new technologies and production processes, such as modern biotechnology, a new breeding or cultivation technique or...3D food printing. Insects, nanomaterials, moulds, algae and new colouring agents are also covered by the regulation. Food that is traditionally consumed in other countries but is new to the EU is also classified as ‘novel’ within the EU market. Examples include seeds or juices from exotic plants, such as chia seeds. Karin Verzijden from legal firm Axon Advocaten: “Nutritional supplements and food with extra additives are subject to detailed rules about what is and isn’t permitted. The composition of a 3D-printed product can change after it is heated, so you also have to consider that. It could mean that the product is subject to the Novel Food Regulation.”

It’s wise for new entrants to the food business to do their homework and find out what’s already known about novel foods: to look whether there is a history of safe use. The Novel Foods Unit of the Netherlands’ Medicines Evaluation Board (www.cbg-meb.nl) supports the Dutch Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sports in assessing new foodstuffs and can help in that process. Karin reminded the audience that authorisation is now generic rather than being linked to an individual as it used to be: “Many entrepreneurs wonder whether they would be better to wait until one of their competitors has got approval. It can seem unfair if you’re the one investing in authorisation, only for others to subsequently benefit from all your hard work. Nevertheless, I think there’s a big advantage in being the first; it gives you a huge head start over the rest of the market.”

According to Natalie Becker, a scientist at Germany’s Federal Office of Consumer Protection and Food Safety (BVL), no specific regulations are necessary for 3D-food-printing machines. “The ‘food safety first’ concept also applies to 3D-printed food,” she said. “Machines, printing materials and finished products simply have to comply with all the current legislation. A CE mark is mandatory. And consider things like HACCP, food labelling, GMO – the list is long, but it’s not new.”

So it’s clear that there are more than enough challenges, and also that a huge amount of research (and hence money) is needed. That brings us on to what was probably the key question among most of the conference attendees: is 3D food printing a hype or will it become reality? In other words, is there any money in 3D food printing? Kjeld van Bommel (TNO), who presented a high-tech vision of where things are heading, how we will get around, how we will communicate and what we will eat in the future, said: “In five years from now, I think it will be more common for restaurants to serve 3D-printed food. A 3D food printer makes it a lot easier to produce products that are specifically suitable for one individual – personalised nutrition is on the rise. And then a few more years down the line, once one printer can handle lots of different kinds of products, that’s when consumers will really start 3D-printing their food at home.”

Nesli Sozer (VTT Technical Research Centre of Finland Ltd.), who is working on improving the composition and textures of 3D-printed food, also referred to the fact that this technology will make it easier to meet the various wants and needs of a large and diverse group of highly demanding consumers. “Over the coming years, more and more people will know their own DNA profile,” was her prediction. “In combination with all the information about the amount of exercise you get each day, your flavour preferences and the things you should avoid and/or actually need for health and lifestyle reasons, 3D food printing gives us the opportunity to create food that is truly tailored to the individual. Today’s production techniques in the food industry are focused on manufacturing large volumes of one type of product, and rapid changeovers from one formulation to another aren’t easy. The 3D food printer will make this new style of mass production more efficient. Before long, energy bars will be aligned with personal profiles. Plus we’ll be able to create completely new mouth-feel experiences…but we can still only dream of that for now.”

In conclusion, most of the researchers expect to make considerable progress in the short term (Sözer mentioned a time frame of 2.5 years), both in the development of printing materials and in improving the hardware and software needed for 3D food printing. The opportunities lie primarily in the realm of personalised nutrition, the development of special food such as lactose-free or fat-free, and in custom-made production. But how long will it take until a whole new market emerges – a market of pre-filled cartridges for 3D food printers, both for consumers and manufacturers? So far, that’s anyone’s guess.

Source: Foto taart: ©Emiel de Lange/Shutterstock.com, foto's met chocolade: ©Tinxi/Shutterstock.com, foto deeg: ©Jakajima bv